Ed. Note: this post is in my voice, but it was co-written with Kevin Jamieson. Kevin provided the awesome plots too.

It’s all the rage in machine learning these days to build complex, deep pipelines with thousands of tunable parameters. Now, I don’t mean parameters that we learn by stochastic gradient descent. But I mean architectural concerns, like the value of the regularization parameter, the size of a convolutional window, or the breadth of a spatio-temporal tower of attention. Such parameters are typically referred to as hyperparameters to contrast against the parameters learned during training. These structural parameters are not learned, but rather descended upon by a lot of trial-and-error and fine tuning.

Automating such hyperparameter tuning is one of the most holy grails of machine learning. And people have tried for decades to devise algorithms that can quickly prune bad configurations and maximally overfit to the test set. This problem is ridiculously hard, because the problems in question become mixed-integer, nonlinear, and nonconvex. The default approach to the hyperparameter tuning problem is to resort to black-box optimization where one tries to find optimal settings by only receiving function values and not using much other auxiliary information about the optimization problem.

Black-box optimization is hard. It’s hard in the most awful senses of optimization. Even when we restrict our attention to continuous problems, black-box optimization is completely intractable in high dimensions. To guarantee that you are within a factor of two of optimality requires an exponential number of function evaluations. Roughly the number of queries scales as $O(2^d)$ where $d$ is the dimension. What’s particularly terrible is that it easy to construct “needle-in-the-haystack” problems where this exponential complexity is real. That is, where no algorithm will ever find a good solution. Moreover, it is hard to construct an algorithm that outperforms random guessing on these problems.

Bayesian inference to the rescue?

In recent years, I have heard that there has been a bit of a breakthrough for hyperparameter tuning based on Bayesian optimization. Bayesian optimizers model the uncertainty of the performance of hyperparameters using priors about the smoothness of the hyperparameter landscape. When one tests a set of parameters, the uncertainty of the cost near that setting shrinks. Bayesian optimization then tries to explore places where the uncertainty remains high and the prospects for a good solution look promising. This certainly sounds like a sensible thing to try.

Indeed, there has been quite a lot of excitement about these methods, and there has been a lot of press about how well these methods work for tuning deep learning and other hard machine learning pipelines. However, recent evidence on a benchmark of over a hundred hyperparameter optimization datasets suggests that such enthusiasm really calls for much more scrutiny.

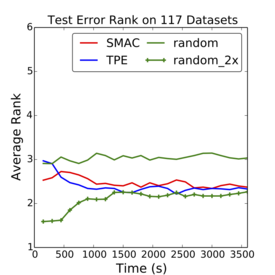

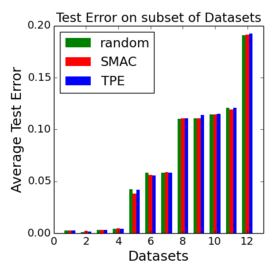

The standard way these methods are evaluated in papers is by using rank plots. Rank plots aggregate statistics across datasets for different methods as a function of time: at a particular time, the solver with the best setting gets one point, the algorithm in second place two points, and so forth. Consider the following plots:

On the left, we show the rank chart for all algorithms and on the right, we show the actual achieved function values of the various algorithms. The first plot represent the average score across 117 datasets collected by Feurer et. al. NIPS 2015 (lower is better). For clarity, the second plot is for a subset of these data sets, but all of the data sets have nearly identical results. We compare state-of-the-art Bayesian optimization methods SMAC and TPE to the method I suggested above: random search where we just try random parameter configurations and don’t use any of the prior experiments to help pick the next setting.

What are the takeaways here? While the rank plot seems to suggest that state-of-the-art Bayesian optimization methods SMAC and TPE resoundingly beat random search, the bar plot shows that they are achieving nearly identical test errors! That is, SMAC and TPE are only a teensy bit better than random search. Moreover, and more troubling, Bayesian optimization is completely outperformed by random search run at twice the speed. That is, if you just set up two computers running random search, you beat all of the Bayesian methods.

Why is random search so competitive? This is just a consequence of the curse of dimensionality. Imagine that your space of hyperparameters is the unit hypercube in some high dimensional space. Just to get the Bayesian uncertainty to a reasonable state, one has to essentially test all of the corners, and this requires an exponential number of tests. What’s remarkable to me is that the early theory papers on Bayesian optimization are very up front about this exponential scaling, but this seems to be ignored by the current excitement in the Bayesian optimization community.

There are three very important takeaways here. First, if you are planning on writing a paper on hyperparameter search, you should compare against random search! If you want to be even more fair, you should compare against random search with twice the sampling budget of your algorithm. Second, if you are reviewing a paper on hyperparameter optimization that does not compare to random search, you should immediately reject it. And, third, as a community, we should be devoting a lot of time to accelerating pure random search. If we can speed up random search to try out more hyperparameter settings, perhaps we can do even better than just running parallel instances of random search.

In my next post, I’ll describe some very nice recent work by Lisha Li, Kevin Jamieson, Giulia DeSalvo, Afshin Rostamizadeh, and Ameet Talwalkar on accelerating random search for iterative algorithms common in machine learning workloads. I will dive into the details of their method and show how it is very promising for quickly tuning hyperparameters.