Ed. Note: Ali Rahimi and I won the test of time award at NIPS 2017 for our paper “Random Features for Large-scale Kernel Machines”. This post is the text of the acceptance speech we wrote. An addendum with some reflections on this talk appears in the following post.

Video of the talk can be found here.

It feels great to get an award. Thank you. But I have to say, nothing makes you feel old like an award called a “test of time”. It’s forcing me to accept my age. Ben and I are both old now, and we’ve decided to name this talk accordingly.

Back When We Were Kids

We’re getting this award for this paper. But this paper was the beginning of a trilogy of sorts. And like all stories worth telling, the good stuff happens in the middle, not at the beginning. If you’ll put up with my old man ways, I’d like to tell you the story of these papers, and take you way back to NIPS 2006, when Ben and I were young spry men and dinosaurs roamed the earth.

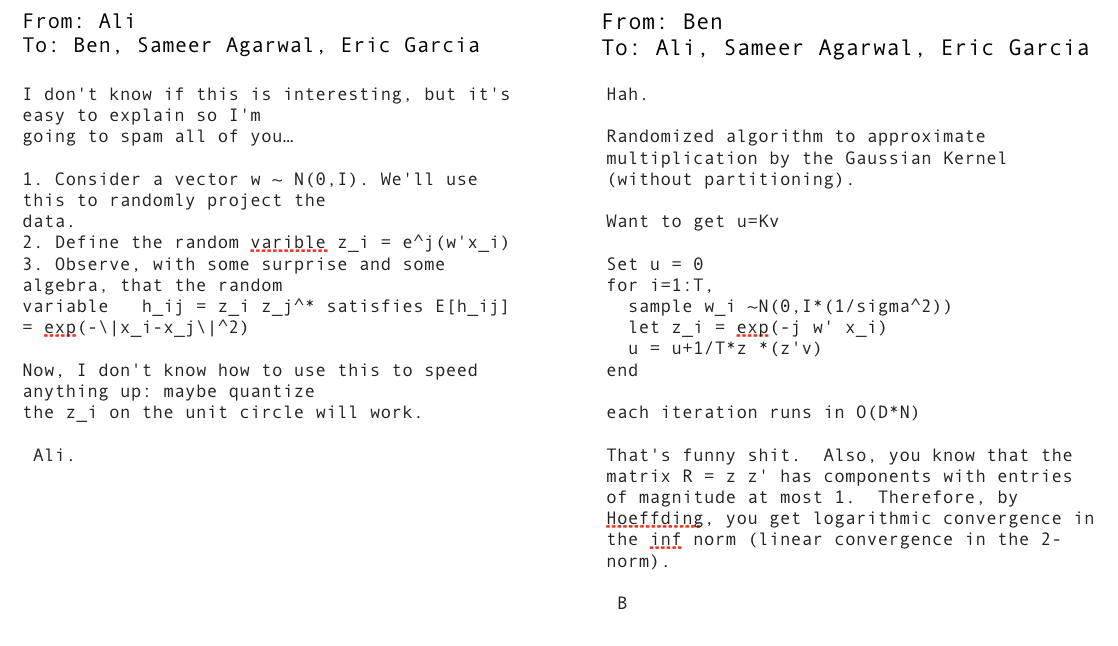

Deep learning had just made a splash at NIPS 2006. The training algorithms were complicated, and results were competitive with linear models like PCA and linear SVMs. In a hallway conversation, people were speculating how they’d fare against kernel SVMs. But at the time, there was no easy way to train kernel SVMs on large datasets. Ben and I had both been working on randomized algorithms (me for bipartite graph matching, Ben for compressed sensing), so after we got home, it took us just two emails to nail down the idea for how to train large kernel SVMs. These emails became the first paper:

Everything about the kitchen sink

To fit a kernel SVM, you normally fit a weighted sum of Radial Basis Functions to data:

\[f(x;\alpha) = \sum_{i=1}^N \alpha_i k(x, x_i)\]We showed how to approximate each of these basis functions in turn as a sum of some random functions that did not depend on the data:

\[k(x,x') \approx \sum_{j=1}^D z(x;\omega_j) z(x'; \omega_j)\]A linear combination of a linear combination is another linear combination, but with this new linear combination has many fewer ($D$) parameters:

\[f(x;\alpha) \approx \sum_{j=1}^D \beta_i z(x;\omega_j)\]We showed how to approximate a variety of radial basis functions and gave bounds for how many random functions you need to approximate them each of them well.

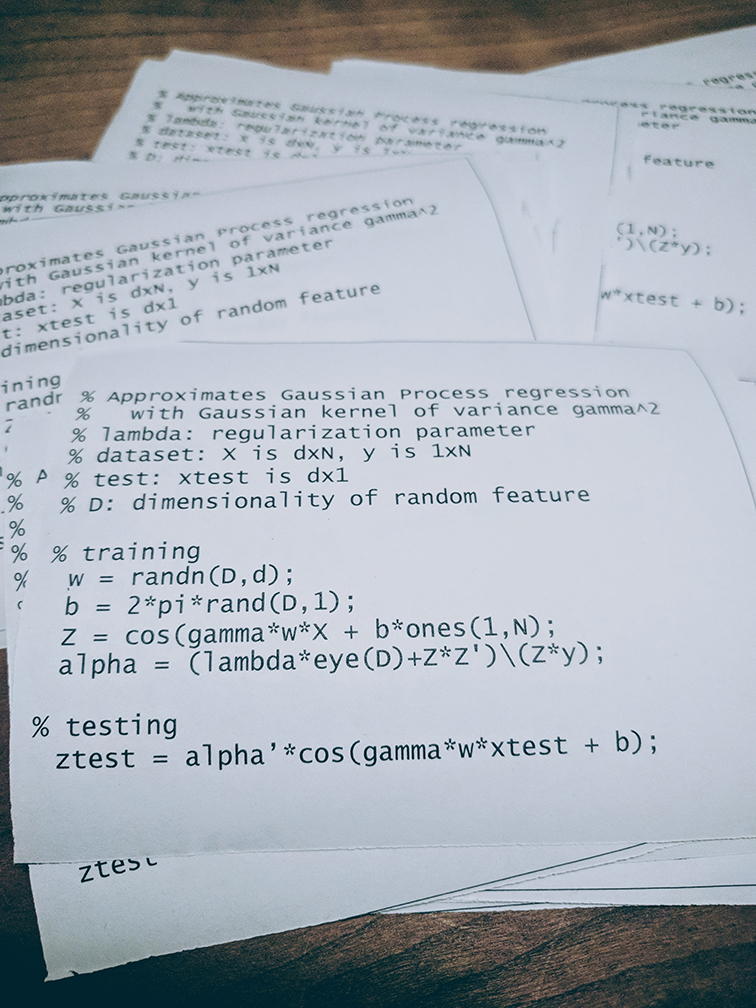

And the trick worked amazingly well in practice. But when it came time to compare it against deep nets, we couldn’t find a dataset or code base that we could train or compare against. Machine Learning was just beginning to become reproducible. So even though we’d started all this work to curb the deep net hype in its tracks, we couldn’t find anything to quash. Instead, we compared against boosting and various accelerated SVM techniques, because that’s what was reproducible at the time. To show off how simple this algorithm was, during NIPS, we handed out these leaflets, that explained how to train kernel SVMs with three lines of MATLAB code. A bit of guerilla algorithm marketing:

But there was something shady in this story. According to this bound, which is tight, to approximate a kernel well, say 1% uniform error, you need tens of thousands of random features. But in all of our experiments, we were getting great results with a only few hundred random features. Sometimes, random feature produced predictors that had better test error than the SVM we were trying to approximate! In other words, it wasn’t necessary to approximate kernels to get good test errors at all.

There seems to be something dodgy with the Random Features story I’ve been telling you so far.

The NIPS Rigor Police

In those days, NIPS had finished transitioning away from what Sam Roweis used to call an “ideas conference”. Around that time, we lived in fear of the tough questions from the NIPS rigor police who’d patrol the poster sessions: I’m talking about Nati Srebro, Ofer Dekel, or Michael Jordan’s students, or god forbid, if you’re unlucky, Shai Ben-David, or, if you’re really unlucky, Manfred Warmuth.

We decided to submit the paper with this bit of dodginess. But the NIPS rigor police kept us honest. We developed a solid understanding of what was happening. We draw a set of random functions iid, then linearly combine them into a predictor that minimize a training loss.

Our second paper said this: In a similar way Fourier functions form a basis for the space of L2 functions, or similar to how wide three layer neural nets can represent any smooth function, random sets of smooth functions, with very high probability, form a basis set for a ball of functions in L2. You don’t need to talk about random features as eigenfunctions for any famous RBF kernels to be sensible. Random functions are a basis set of a Hilbert space that was legitimate by itself. In our third paper, we finally analyzed the test error of this algorithm when it’s trained on set of samples.

By this third paper, we’d entirely stopped thinking in terms of kernels, and just fitting random basis function to data. We put on solid foundation the idea of linearly combining random kitchen sinks into a predictor. Which meant that it didn’t really bother us if we used more features than data points.

Our original goal had been to compare deep nets against kernel SVMs. We couldn’t do it back then. But code and benchmarks are abundant now, and direct comparisons are easy. For example, Avner May and his collaborators have refined the technique and achieved results comparable to deep nets on speech benchmarks. Again, not bad for just four lines of MATLAB code.

I sometimes use random features in my job. I like to get creative with special-purpose random features. It’s such an easy thing to try. When they work and I’m feeling good about life, I say “wow, random features are so powerful! They solved this problem!” Or if I’m in a more somber mood, I say “that problem was trivial. Even random features cracked it.” It’s the same way I think about nearest neighbors. When nearest neighbors cracks a dataset, you either marvel at the power of nearest neighbors, or you conclude your problem wasn’t hard at all. Regardless, it’s an easy trick to try.

KIDS THESE DAYS

It’s now 2017. I find myself overwhelmed with the field’s progress. We’ve become reproducible. We share code freely and use common task benchmarks.

We produce stunningly impressive results: Self-driving cars seem to be around the corner, artificial intelligence tags faces in photos, transcribes voicemails, translates documents, and feeds us ads. Billion-dollar companies are built on machine learning. In many ways, we’re in a better spot than we were 10 years ago. In some ways, we’re in a worse spot.

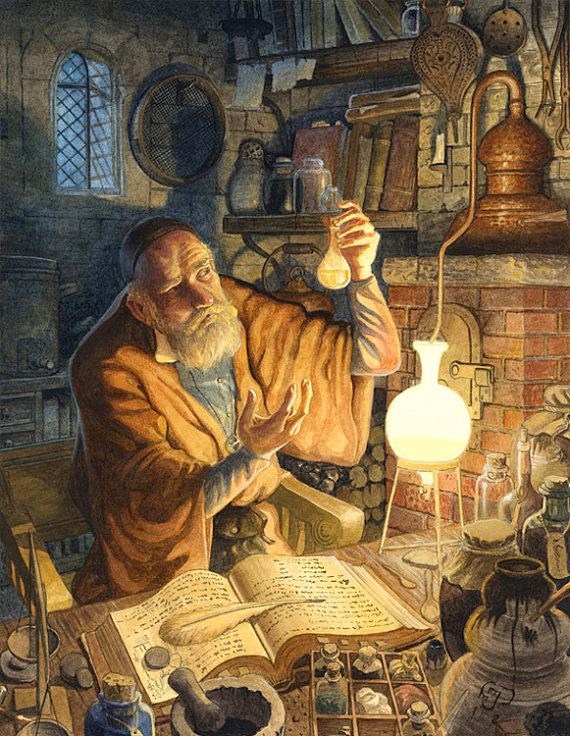

There’s a self-congratulatory feeling in the air. We say things like “machine learning is the new electricity”. I’d like to offer an alternative metaphor: machine learning has become alchemy.

Alchemy’s ok. Alchemy’s not bad. There’s a place for alchemy. Alchemy worked.

Alchemy worked

Alchemists invented metallurgy, ways to make medication, dying techniques for textiles, and our modern glass-making processes.

Then again, alchemists also believed they could transmute base metals into gold and that leeches were a fine way to cure diseases. To reach the sea change in our understanding of the universe that the physics and chemistry of the 1700s ushered in, most of the theories alchemists developed had to be abandoned.

If you’re building photo sharing services, alchemy is fine. But we’re now building systems that govern health care and our participation in civil debate. I would like to live in a world whose systems are build on rigorous, reliable, verifiable knowledge, and not on alchemy. As aggravating as the NIPS rigor police was, I wish it would come back.

I’ll give you an example of where this hurts us.

SGD (and variants) are all you need ‘BECAUSE MACHINE LEARNING NOISE FLOOR’

I bet a lot of you have tried training a deep net of your own from scratch and walked away feeling bad about yourself because you couldn’t get it to perform.

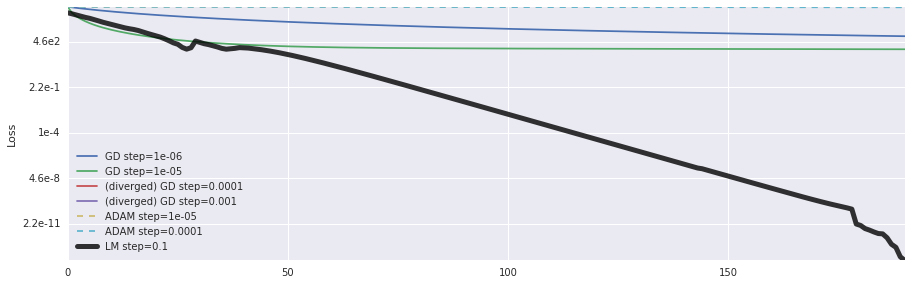

I don’t think it’s your fault. I think it’s gradient descent’s fault. I’m going to run gradient descent on the simplest deep net you can imagine, a two layer deep net with linear activations and where the labels are a badly-conditioned linear function of the input.

\[\min_{W_1,W_2} \hat{\mathbb{E}}_x \| W_1 W_2 x - A x\|^2\]

Here, the condition number of A is $10^{20}$. Gradient descent makes great progress early on, then spends the rest of the time making almost no progress at all. You might think this it’s hit a local minimum. It hasn’t. The gradients aren’t decaying to 0. You might say it’s hitting a statistical noise floor of the dataset. That’s not it either. I can compute the expectation of the loss and minimize it directly with gradient descent. Same thing happens. Gradient descent just slows down the closer it gets to a good answer. If you’ve ever trained Inception on ImageNet, you’ll know that gradient descent gets through this regime in a few hours, and takes days to crawl through this regime.

The black line is what a better descent direction would do. This is Levenberg-Marquardt.

If you haven’t tried optimizing this problem with gradient descent, please spend 10 minutes coding this up or try out this Jupyter notebook. This is the algorithm we use as our workhorse, and it fails on a completely benign non-contrived problem. You might say “this is a toy problem, gradient descent fits large models well.” First, everyone who raised their hands a minute ago would say otherwise. Secondly, this is how we build knowledge, we apply our tools to simple problems we can analyze, and work our way up in complexity. We seem to have just jumped our way up.

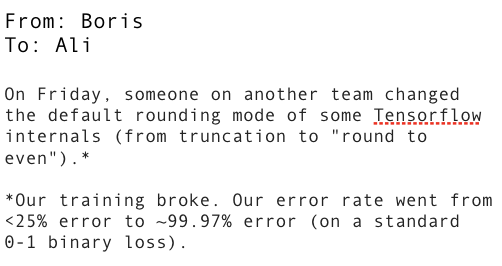

This pain is real. Here’s an email that landed in my inbox two weeks ago from my friend Boris:

This experience is not unique. There are numerous bugs like this out there on various forums. This happens because we run the wrong optimizers on loss surfaces we don’t understand. Our solution is to add more mystery to an already mysterious scaffolding. Like Batch Norm.

Reducing internal covariate shift

Batch Norm is a technique that speeds up gradient descent on deep nets. You sprinkle it between your layers and gradient descent goes faster. I think it’s ok to use techniques we don’t understand. I only vaguely understand how an airplane works, and I was fine taking one to this conference. But it’s always better if we build systems on top of things we do understand deeply? This is what we know about why batch norm works well. But don’t you want to understand why reducing internal covariate shift speeds up gradient descent? Don’t you want to see evidence that Batch Norm reduces internal covariate shift? Don’t you want to know what internal covariate shift is? Batch Norm has become a foundational operation for machine learning. It works amazingly well. But we know almost nothing about it.

What’d Your Mother Say?

Our community has a new place in society. If any of what I’ve been saying resonates with you, let me suggest some just two ways we can assume our new place responsibly.

Think about how many experiments you’ve run in the past year to crack a dataset for sport, or to see if a technique would give you a boost. Now think about the experiments you ran to help you find an explanation for a puzzling phenomenon you observed. We do a lot of the former. We could use a lot more of the latter. Simple experiments and simple theorems are the building blocks that help understand complicated larger phenomena.

“It seems easier to train a bi-directional LSTM with attention than to compute the SVD of a large matrix”. - Chris Re

For now, most of our mature large scale computational workhorses are variants of gradient descent. Imagine the kinds of models and optimization algorithms we could explore if we had commodity large scale linear system solvers or matrix factorization engines. We don’t know how to solve this problem yet, but one worth solving. We are the group who can solve it.

Over the years, some of my dearest friends and strongest relationships have emerged from this community. My gratitude and love for this group are sincere, and that’s why I’m up here asking us to be rigorous, less alchemical. Ben and I are grateful for the award, and the opportunity to have gotten to know many of you. And we hope that you’ll join us to grow machine learning beyond alchemy into electricity.