The first machine learning benchmark dates back to the late 1950s. Few used it and even fewer still remembered it by the time benchmarks became widely used in machine learning in the late 1980s.

In 1959 at Bell Labs, Bill Highleyman and Louis Kamenstky designed a scanner to evaluate character recognition techniques. Their goal was “to facilitate a systematic study of character-recognition techniques and an evaluation of methods prior to actual machine development.” It was not clear at the time which part of the computations should be done in special purpose hardware and which parts should be done with more general computers. Highleyman later patented an OCR scheme that we recognize today as a convolutional neural network with convolutions optically computed as part of the scanning.

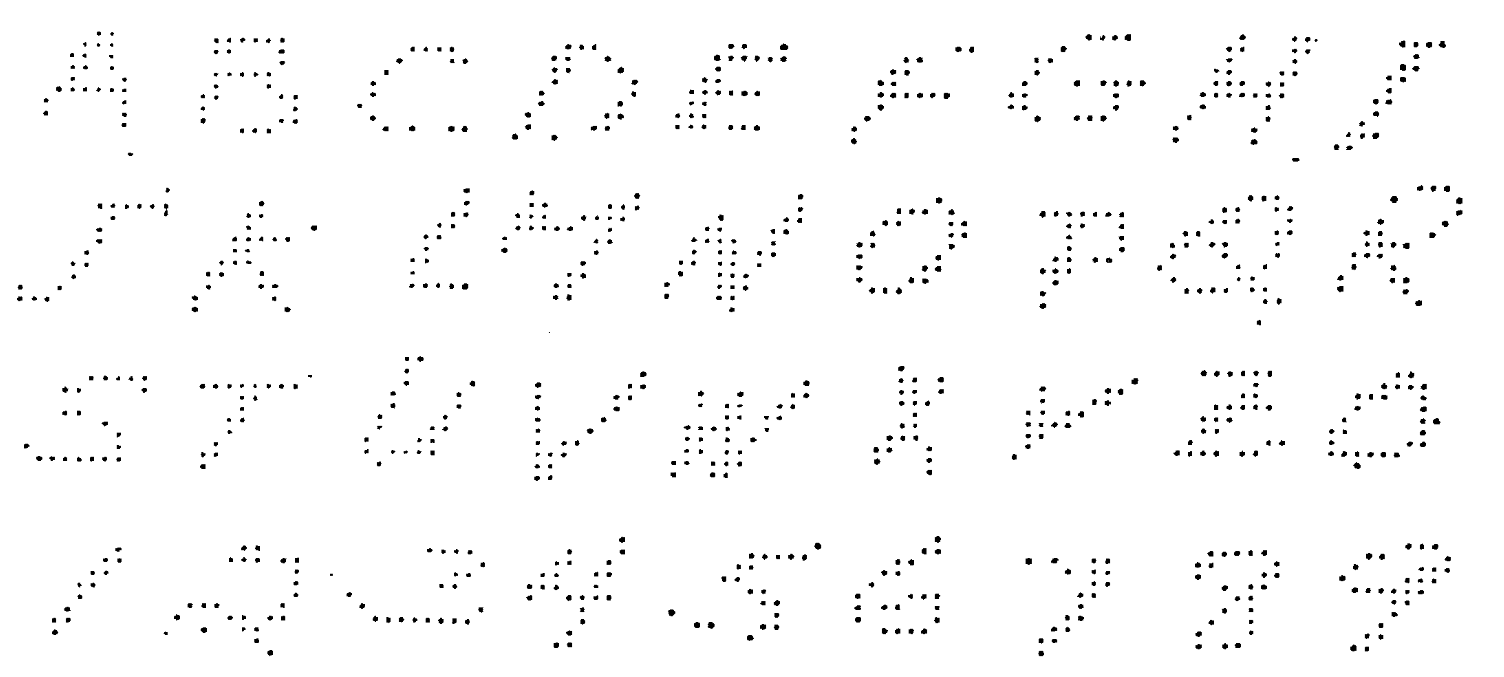

Highleyman and Kamentsky used their scanner to create a dataset of 1800 alphanumeric characters. They gathered the 26 letters of the alphabet and 10 digits from 50 different writers. Each character in their corpus was scanned in binary at a resolution of 12 x 12 and stored on punch cards that were compatible with the IBM 704, the GPGPU of the era.

With the data in hand, Highleyman and Kamenstky began studying various proposed techniques for recognition. In particular, they analyzed a method of Woody Bledsoe and published an analysis claiming to be unable to reproduce Bledsoe’s results. Bledsoe found their numbers to be considerably lower than he had expected, and asked Highleyman to send him the data. Highleyman obliged, mailing the package of punch cards across the country to Sandia Labs.

Upon receiving the data, Bledsoe conducted a new experiment. In what may be the first implementation of a train-test split, he divided the characters up, using 40 writers for training and 10 for testing. By tuning the hyperparameters, Bledsoe was able to achieve approximately 60% error. Bledsoe also suggested that the high error rates were to be expected as Highleyman’s data was too small. Prophetically, he declared that 1000 alphabets might be needed for good performance.

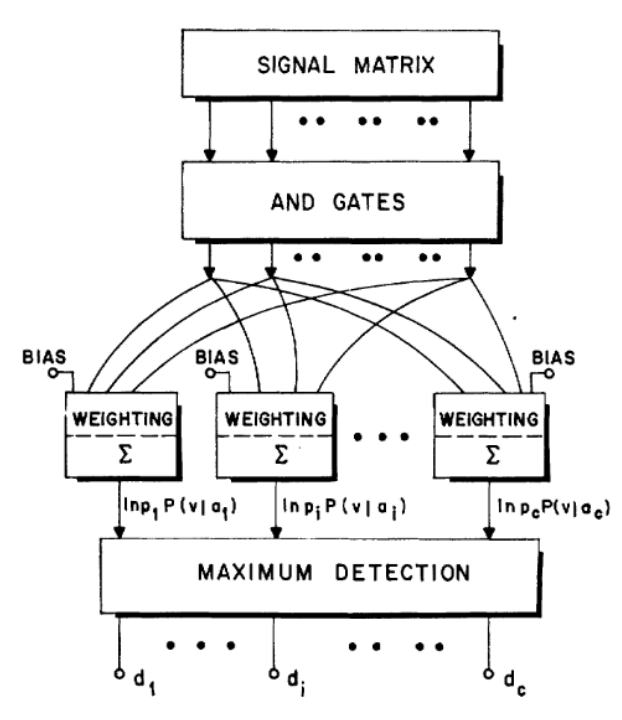

By this point, Highleyman had also shared his data with Chao Kong “C.K.” Chow at the Burroughs Corporation (a precursor to Unisys). A pioneer of using decision theory for pattern recognition, Chow built a pattern recognition system for characters. Using the same train-test split as Bledsoe, Chow obtained an error rate of 41.7% using a convolutional neural network.

Highleyman made at least six additional copies of the data he had sent to Bledsoe and Chow, and many researchers remained interested. He thus decided to publicly offer to send a copy to anyone willing to pay for the duplication and shipping fees. An interested party would simply have to mail him a request. Of course, the dataset was sent by US Postal Service. Electronic transfer didn’t exist at the time, resulting in sluggish data transfer rates on the order of a few bits per minute.

Highleyman not only created the first machine learning benchmark. He authored the the first formal study of train-test splits and proposed empirical risk minimization for pattern classification as part of his 1961 dissertation. By 1963, however, Highleyman had left his research position at Bell Labs and abandoned pattern recognition research.

We don’t know how many people requested Highleyman’s data. The total number of copies may have been less than twenty. Based on citation surveys, we determined there were at least another six copies made after Highleyman’s public offer for duplication, sent to CMU, Honeywell, SUNY Stony Brook, Imperial College, UW Madison, and Stanford Research Institute (SRI).

The SRI team of John Munson, Richard Duda, and Peter Hart performed some of the most extensive experiments with Highleyman’s data. A 1-nearest-neighbors baseline achieved an error rate of 47.5%. With a more sophisticated approach, they were able to do significantly better. They used a multi-class, piecewise linear model, trained using Kesler’s multi-class version of the perceptron algorithm (what we’d now call “one-versus all classification”). Their feature vectors were 84 simple pooled edge detectors in different regions of the image at different orientations. With these features, they were able to get a test error of 31.7%, 10 percentage points better than Chow. When restricted only to digits, this method recorded 12% error. The authors concluded that they needed more data, and that the error rates were “still far too high to be practical.” They concluded that “larger and higher-quality datasets are needed for work aimed at achieving useful results.” They suggested that such datasets “may contain hundreds, or even thousands, of samples in each class.”

Munson, Duda, and Hart also performed informal experiments with humans to gauge the readability of Highleyman’s characters. On the full set of alphanumeric characters, they found an average error rate of 15.7%, about 2x better than their pattern recognition machine. But this rate was still quite high and suggested the data needed to be of higher quality. They (again prophetically) concluded that “an array size of at least 20X20 is needed, with an optimum size of perhaps 30X30.”

Decades passed until such a dataset appeared. Thirty years later, with 125 times as much training data, 28x28 resolution, and with grayscale scans, a neural net achieved 0.7% test error on the MNIST digit recognition task. In fact, a similar model to Munson’s architecture consisting of kernel ridge regression trained on pooled edged detectors also achieves 0.6% error. Intuition from the 1960s proved right. The resolution was higher and the number of examples per digit was now in the thousands, just as Bledsoe, Munson, Duda, and Hart predicted would be sufficient. Reasoning heuristically that the test error should be inversely proportional to the square root of the number of training examples, we would expect an 11x improvement over Munson’s approaches. The actual recorded improvement from 12% to 0.7% was closer to 17x, not far from what the back of the envelope calculation predicts.

Unlike Highleyman’s data, MNIST featured only digits, no letters. Only recently, in 2017, researchers from Western Sydney University extracted alphanumeric characters from the NIST-19 repository. The resulting EMNIST_Balanced dataset has 2400 examples in each of the 47 classes, with a class for all upper case letters, all digits, and some of the non-ambiguous lower case letters. Currently, the best performing model achieves a test error rate of 9.4%. While the dataset is still fairly new, this is only a 3x improvement over the methods of Munson, Duda, and Hart. Applying the same naive scaling argument as above, the increase in dataset size would predict a 7x improvement if such an improvement was achievable. Considering that the SRI team observed a human-error rate of 11% on Highleyman’s data, it is quite possible that an accuracy of 90% is close to the best that we can expect for recognizing handwritten digits without context.

The story of Highleyman’s data foreshadows many of the later waves of machine learning research. A desire for better evaluation inspired the creation of novel data. Dissemination of the experimental results on this data led to sharing in order for researchers to be content that the evaluation was fair. Once the dataset was distributed, others requested the data to prove their methods were superior. And then the dataset itself became enshrined as a benchmark for competitive testing. Such comparative testing led to innovations in methods, theory, and data collection and curation itself. We have seen this pattern time and time again in machine learning, from the UCI repository, to MNIST, to ImageNet, to CASP. The nearly forgotten history of Highleyman’s data marks the beginning of this pattern recognition research paradigm.

We are, as always, deeply indebted to Chris Wiggins for sending us Munson et al.’s paper after watching a talk by BR on the history of ML benchmarking. We also thank Ludwig Schmidt for pointing us to EMNIST.

Addendum on our protagonist Bill Highleyman.

After posting this blog, we found some lovely recollections by Bill Highleyman about his thesis. It is remarkable how Bill invented so many powerful machine learning primitives—finding linear functions that minimize empirical risk, gradient descent to minimize the risk, train-test splits, convolutional neural networks—all as part of his PhD dissertation project. That said, Bill considered the project to be a failure. He (and Bell Labs) realized the computing of 1959 was not up to the task of character recognition.

After he finished his thesis, Bill abandoned pattern recognition and moved on to work on other cool and practical computer engineering projects that interested him, never once looking back. By the mid sixties Bill had immersed himself in data communication and transmission, and patented novel approaches to electrolytic printing and financial transaction hardware. He eventually ended up specializing in high-reliability computing. Though he developed many of the machine learning techniques we use today, he was content to leave the field and work to advance general computing to catch up with his early ideas.

It’s odd but not surprising that while every machine learning class mentions Rosenblatt, Minsky, and Papert, almost everyone we’ve spoken with so far has never heard of Bill Highleyman.

We worry Bill is no longer reachable as he seems to have no online presence after 2019 and would be 88 years old today. If anyone out there on has met Bill, we’d love to hear more about him. Please drop us a note.

And if anyone has any idea of where we can get a copy of his 1800 characters from 1959, please let us know about that too…