One of the central tenets of machine learning warns the more times you run experiments with the same test set, the more you overfit to that test set. This conventional wisdom is mostly wrong and prevents machine learning from reconciling its inductive nihilism with the rest of the empirical sciences.

Rebecca Roelofs, Ludwig Schmidt, and Vaishaal Shankar led an passionate quest to test the overfitting hypothesis, devoting countless hours to reproducing machine learning benchmarks. In particular, they painstakingly recreated a test set of the famous ImageNet benchmark, which itself is responsible for bringing about the latest AI feeding frenzy. Out of the many surprises in my research career, what they found surprised me the most.

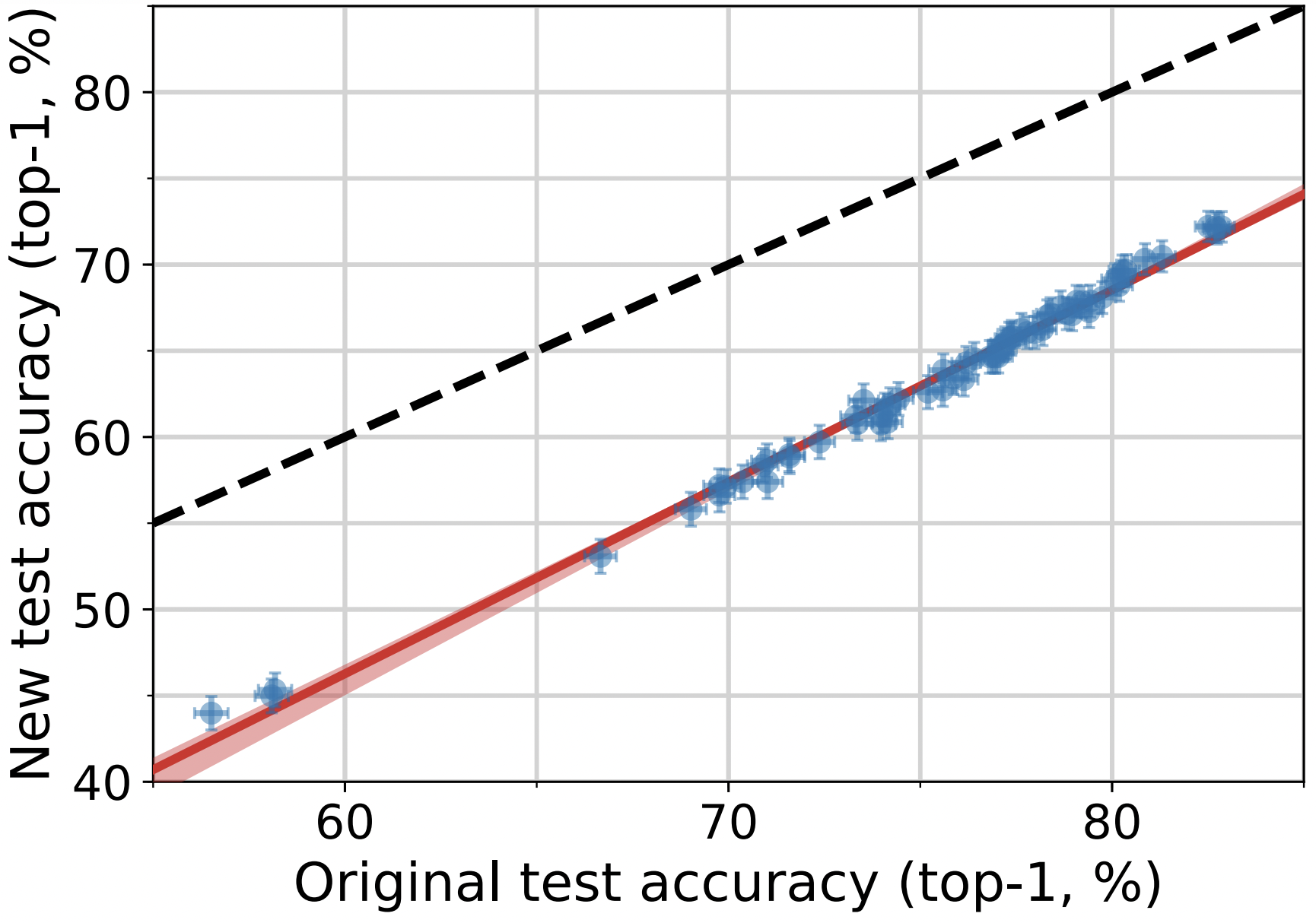

In this graph, the x-axis is the accuracy on the original ImageNet benchmark, which has been used millions of times by individual researchers at Google alone. On the y-axis is the accuracy evaluated on “ImageNet v2” set, which was made by closely trying to replicate the data creation method for the benchmark. Each blue dot represents a single machine learning model trained on the original ImageNet data. The red line is a linear fit to these models, and the dashed line is what we would see if the accuracy was the same on both test sets. What do we see? The models which perform the best on the original test set perform the best on the new test set. That is, there is no evidence of overfitting.

What is clear, however, is a noticeable drop in performance on the new test set. Despite their best efforts in reproducing the ImageNet protocol, there is evidence of a distribution shift. Distribution shift is a far reaching term describing whenever the data on which a machine learning algorithm is deployed is different from the data on which it is trained. The Mechanical Turk workers who labeled the images were different from those originally employed. The API used for the labeling was slightly different. The selection mechanism to aggregate differences in opinions between labelers is slightly different. The small differences add up to around a 10% drop in accuracy, equivalent to five years of progress on the benchmark.

Folks in my research group have reproduced this phenomenon several times. In Kaggle competitions, where the held out set and validation set were identically distributed, we saw no overfitting and no distribution shift. We found sensitivity to distribution shifts in CIFAR10, in video, and in question answering benchmarks. And Chhavi Yadav and Leon Bottou showed that we have not yet overfit to the venerable MNIST data set, but distribution shift remains a challenge.

The marked sensitivity to distribution shift is a huge issue. If small ambiguities in reproductions lead to large losses in predictive performance, what happens when we take ML systems designed on static benchmarks and deploy them in important applications? A decade of AI fever has delivered piles of evidence that distribution shift is machine learning’s achilles heel. Algorithms run inside the big tech companies need to be constantly retrained with their huge computing resources. Data-driven algorithms for radiology often fail if one changes the X-ray machine. AI algorithms for sepsis fail if you change hospitals. And self-driving car systems are readily confused in new environments (No citation needed. Keep your Tesla away from me.).

The only way forward is for machine learning to engage more broadly with other scientists who have been tackling similar issues for centuries. My first proposal is simple: let’s change our terminology to align with the rest of the sciences. The study of distribution shift in machine learning has always been insular and, while machine learning is particularly sensitive, all empirical science must deal with the jump from experiment to reality.

With this in mind, Deb Raji and I have been digging through the scientific literature for a while now hoping to find some answers. In most other parts of science, “robustness to distribution shift” is called external validity. External validity quantifies how well a finding generalizes beyond a specific experiment. For example, a significant result on a particular cohort may not generalize to a broader population.

Predictive algorithms and experimental science both rely on repeatability. “The sun has always risen in the east.” “The apple always falls straight to the ground.” We expect that given the same contexts, the natural world more or less repeats itself. There is unfortunately a big leap from the sun rising in the morning, to an experimental finding in machine learning or biomedicine being reproducible. Why?

The experimental contexts under which predictions and inferences are designed are often far too narrow. The results of a study performed on young male college students in Maine may not help us understand properties of a retirement community in Arizona. These populations are different! However, it may give us insights into other cohorts of male college students: a study at Bates may generalize to Colby or Bowdoin.

Contexts can change in a myriad of ways. Some examples include the following:

- The context can just be too narrow in the experiment. Do studies on adults generalize to children? Do studies on medications with only men generalize to women?

- The measured quantity may itself change. It is often easier to measure, detect, and control for exogenous disturbances in a lab setting than in the real world.

- Populations can change over time. For example, medical recommendations from the 1980s may no longer apply to the current population. Recent developments have led to not recommending aspirin to prevent heart attacks. Machine Learners like to call this covariate shift.

- Even more nefariously, the population can change in response to the intervention. A classic example of this is Goodhart’s Law which states “Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.”

How can we grapple with these external validity challenges? Verifying external validity is daunting and the set of potential solutions remains quite limited. As I mentioned, Deb and I have been chatting about this for a year now, and we’ve now dragged the rest of the group into our investigations. So I’m going to share the blog with Deb for a few posts now, and we’ll both expand on what we’ve been reading and thinking about. In the next few posts, we’ll explore some of the intricacies of when external validity can fail and will also try to spell out some of the research directions that might help bridge the gaps between experiments and reality.